The Munker-White Illusion: Why Our Eyes Can’t Always Be Trusted

A Study in Perception, Context, and Visual Processing

Image by Lloyd TheCheeseKing - Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113065095

There are few things more certain in life than what we see with our own eyes. Sight gives us a sense of grounding, a daily dose of reality. But what if even that certainty is a mirage? What if colour, brightness, and form—those building blocks of visual truth—could lie to us? Welcome to the peculiar world of the Munker-White illusion, where perception bends and certainty wavers.

The Illusion That Deceives the Eye

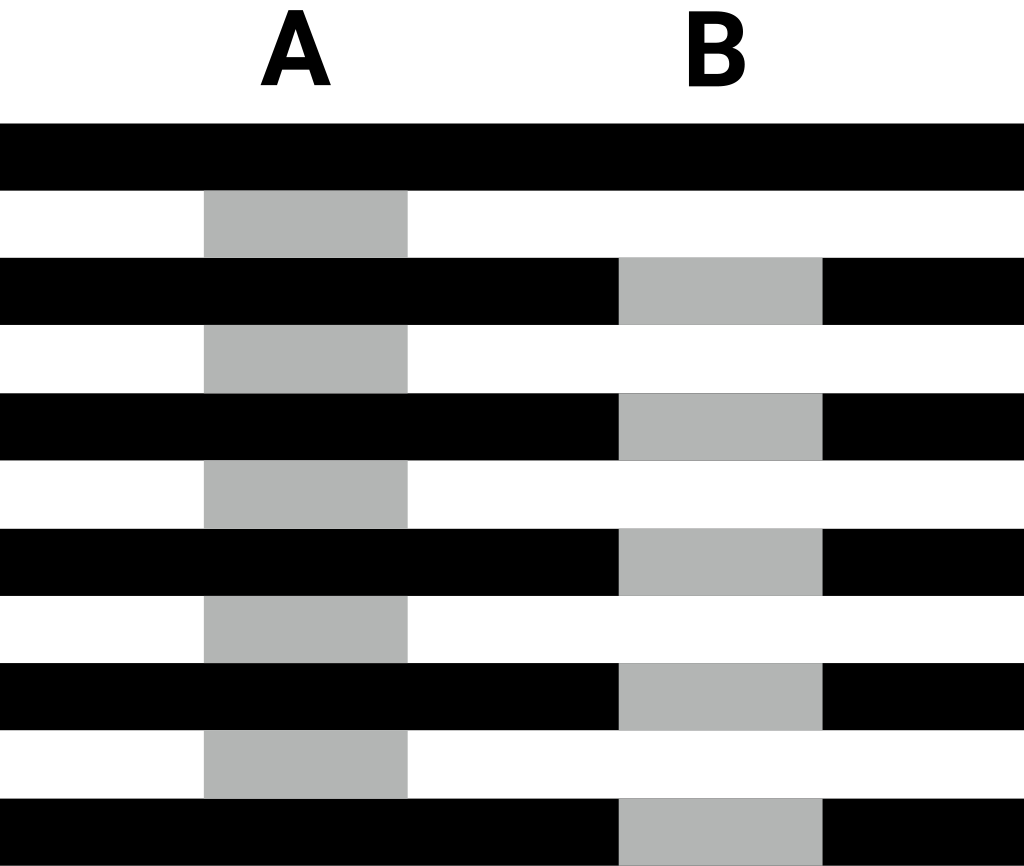

At first glance, the Munker-White illusion appears innocent: a collection of coloured bars over a striped background. But stare a moment longer and you’ll notice something strange—identical bars appear to be different colours or shades, depending solely on their background.

Imagine a red bar placed over alternating green and blue stripes. The bars are all the same red. No tricks, no digital sleight of hand. Yet, as your brain takes in the scene, some bars appear more orange, others more pink. Logic says this shouldn’t be possible. But your eyes—and more importantly, your brain—say otherwise.

A Tale of Two Discoverers

The illusion combines the work of two researchers: Michael White, who introduced White’s illusion in the 1980s, and Dale Purves and colleagues, who explored extensions and variations such as the Munker illusion. Both phenomena demonstrate the same perplexing principle: the context around a colour dramatically changes how we perceive it.

In the Munker version, vertical coloured bars pass through horizontal stripes. As the bars cross light and dark regions, their colours seem to shift. Yet in truth, the RGB values stay constant. The change is not in the screen, but in our minds.

Why It Happens: A Brain Designed for Context

The Munker-White illusion is a triumph of context over fact. Your brain is a meaning-making machine. It doesn’t just read raw data from the eyes; it interprets that data based on surrounding information, lighting, shadows, expectations, and past experiences.

In this case, the brain appears to assign colours based on their relationship to nearby hues. It might be trying to compensate for shadows or lighting differences. Or perhaps it's using mental shortcuts—known as heuristics—to speed up processing. These shortcuts usually work. But every so often, they create illusions that reveal just how much guesswork is involved in seeing.

The Deeper Message in the Illusion

What makes the Munker-White illusion more than just a parlour trick is what it tells us about reality. It’s a reminder that perception is not a passive reception of truth but an active construction of it. We don’t see the world as it is. We see the world as our brain interprets it.

In art, this illusion has inspired fascinating experiments in colour theory and visual design. In psychology, it challenges the assumption that seeing is believing. In neuroscience, it opens up the intricate workings of how the visual cortex processes information.

Final Thoughts

The Munker-White illusion is more than a curiosity; it's a doorway into understanding human perception's complex, often counterintuitive nature. It shows us how easily our senses can be fooled—and how beautiful that deception can be. Next time you marvel at the colours around you, pause and wonder: How much of what I see is really there—and how much is my brain's best guess?

In a world that increasingly demands clarity and certainty, illusions like this remind us of a timeless truth: sometimes, the most honest thing our senses can say is “I’m not so sure.”

As always, feel free to reach out with any questions or comments. Happy musing!